“If this is a poem meant to be read out loud,

what’s silence doing in it, right in the middle,

a great salt pan of silence?”

Adil Jussawala, “About a Black Horse”

Adil Jussawala, in his poem “About a Black Horse” asks this perplexing question. It’s a question that, in a sense, shakes up the poem’s very existence—why does the poem exist the way it does? What would happen to that poem, if the silence in it was taken away? Without the silence, would it still be the same poem?

A simplistic reading would deploy a theory of opposition, that sound does not exist without silence. So if the poem is meant to be read out loud, to literally give voice to words, then it must necessarily carry silences, too. But rather than seeking resolution within Jussawala’s conundrum, I find myself stuck on the question itself.

When I consider what makes a poem a poem, or a dance a dance, I find that describing their materials is insufficient. Just as words do not exist as poems, movement in and of itself does not make a dance. What changes these materials into works of art is the shape, the form we give them.

Form is a slippery term. Often, it is confused with genre, or seen only as a means of classifying ‘art forms’—Bharatanatyam is different from Odissi, both of which are different from Hindustani music. But form is more than taxonomy. It encapsulates the entirety of an artwork—how it looks, feels, is constructed and experienced.

In 1914, the British art critic Clive Bell wrote about “Significant Form,” which was, according to him, “the one quality common to all works of visual art.” He looked at paintings as wholistic entities, and argued that the total visual experience of a painting—its lines, colours, textures—could itself convey feeling; meaning did not lie beyond the work’s own construction. He wrote:

“The distinction between form and colour is an unreal one; you cannot conceive a colourless line or a colourless space; neither can you conceive a formless relation of colours…when I speak of significant form, I mean a combination of lines and colours…that moves me aesthetically.”

Stepping away for a moment from Bell and Formalism with a capital (European) F, I find in his words a more elemental lesson. That form is inseparable from our encounter with art, whether we recognise it or not, whether we admit to it or not.

In my work as a choreographer and poet, I obsess over form. I don’t dance randomly, leap from one part of the stage to another, just because. I might improvise, but I still give thought to each gesture as I dance. Similarly, I might write the first draft of a poem in a great fury, but the poem itself emerges from long nights of editing, parsing through the muck until the poem—both on the page and read aloud—gives me an experience I am not entirely dissatisfied with.

Poems and dances, to me, are formally similar in the sense that they are both built on a series of associations. Poems differ from prose because they are made of lines, not sentences. The poetic line relies on a fracturing—unlike a sentence it does not have to complete itself to convey its meaning. Prose can tell us simply that ‘The torrential rain wrecked a hibiscus bush.’ But poems can say, as Tishani Doshi does:

“Now that damaged petals of hibiscus

Tishani Doshi

drown the terrace stones,

we must kneel together and gather.

This is how desire works:

splintering first, then joining.”

Contemporary dance, too, allows us to experience a series of movements. As one movement follows the other, they don’t form sentences that begin with a capitalisation and end with a punctuation mark. Instead, they give us a fractured journey of bodies through space, whose meaning we construct for ourselves. We build associations between each movement, and between those movements and our worlds outside the theatre—memories, headlines, history.

We often talk about the arc of a performance or the trajectory of a poem. But I see my performances and poems more as composite shapes. Shapes, marked not just by their external boundaries but also by what constitutes them. Both the big things and the little things—the way each movement and each word sits next to the other, and how each movement and word together create resonance.

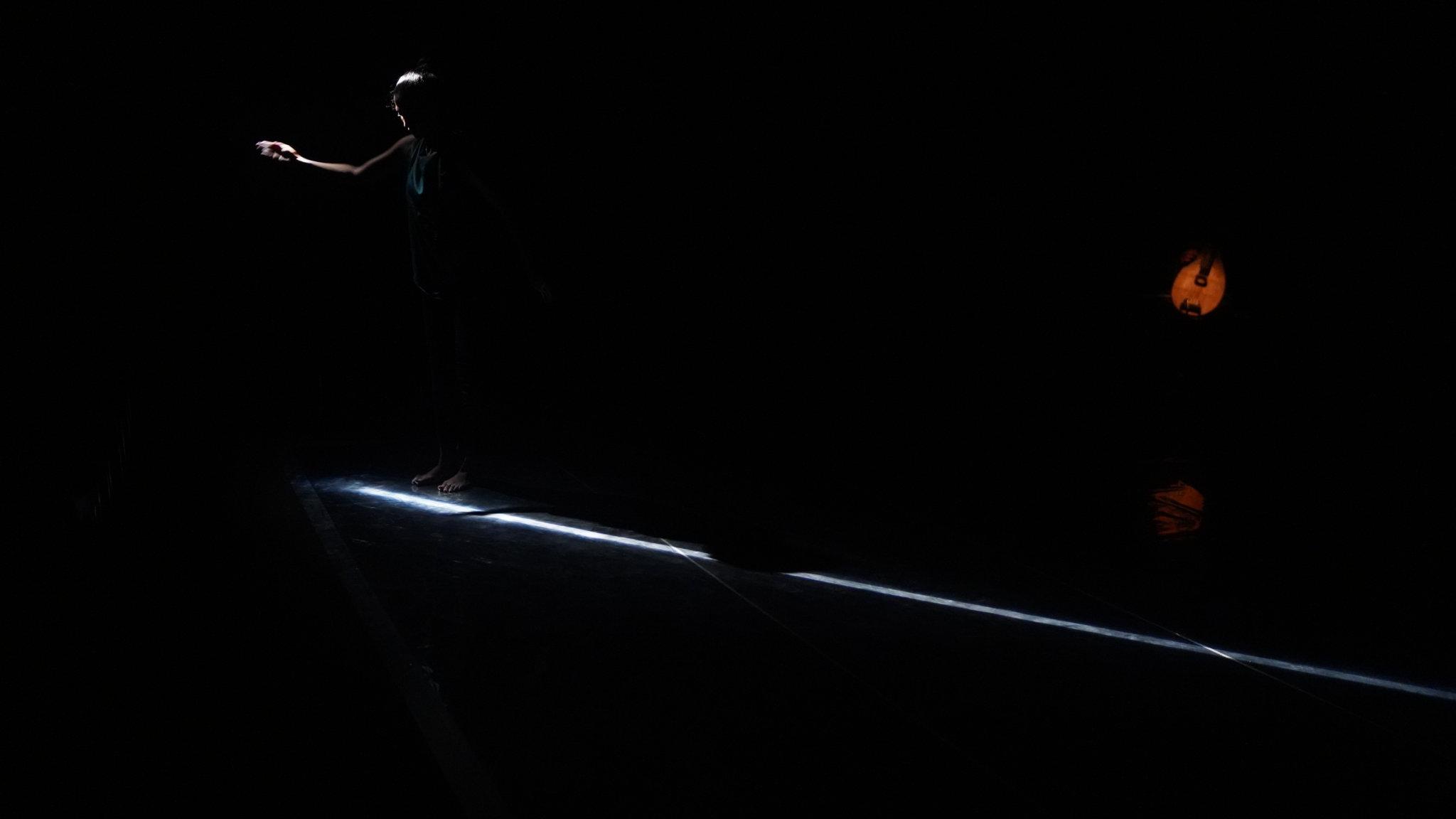

In my most recent performance work, Do You Want Me to Stay for Anything in Particular?, my co-choreographer Sujay Saple and I knew we wanted to make a performance that dealt with loss and absence. But rather than spell out a story of heartbreak or bereavement, we chose instead to, along with the performers, generate a series of visual scores. These same scores allowed the composer to build a reservoir of music, and the dancer, of movement.

Over several weeks, we spliced, overlapped and rearranged the scores. Accordingly, their corresponding sounds and movements shifted around, too.

We worked like this until we had an hour-long piece in which sounds and movements appeared and disappeared, repeated or played just once. And so, we made certain sensory motifs familiar and then pulled them away, evoking loss and absence in the form of the work itself.

There is a myth about form, I think, which is that it concerns only the abstract. And abstraction, in turn, is often pegged as art with a stiff upper lip, something that is hard ‘to get.’ But even the most legible work of art—a bunch of flowers in a vase—has a form, an indication of its being. Moreover, implicit in the disparaging of abstraction is the notion that a work of art is an object, something to be possessed. And if it defies our understanding, we fail to posses it. When a work of art consciously highlights its form (as abstraction, of course, does), it asks us to do something that, surprisingly, remains quite radical—it asks to experience a work, not conquer it.

This isn’t to say that all works of art need to lead us to an emotional experience. The opposite of understanding is not feeling. Thinking can be a process, rather than an accumulation of knowledge. Even if we don’t ‘get’ a work of art, maybe it leaves us asking many questions that refuse to pipe down. The Chennai-based choreographer Preethi Athreya’s contemporary dance piece The Lost Wax Project is one such work. In it, four dancers draw out a large circle, fill it with white powder, then dance within it. As they move in a perfectly timed choreography, we realise that a single dancer never occupies the centre; if anything, the group traverses the centre all at once. This simple negotiation of the shape of a circle made me think about the relationship between power at the centre and power in the margins. I can’t say if the work as a whole was ‘about’ this per se, but to be left with such questions was enough.

I was recently reading a poetry textbook (they do exist!) in which I found a delightful explanation of form: it is “the necessary nothing, the pressure that transforms the ordinary carbon into a diamond.” Just like how in Athreya’s work, the dancers’ pathways transformed a powdery circle into political ground.

Even though form is such an integral part of how we experience any work of art, it is sadly pitted against content. Dances of stories (in both contemporary and classical dance) are made out to be nemeses of dances of form—ones that don’t tell stories, or don’t tell anything, really. But there’s nothing productive about this division. Susan Sontag wrote that in separating form and content, we invariably make “content essential and form accessory.” That is, form is but a mould that carries within it the ‘real point’ of the work. Sontag warns against this assumption:

“Art is not only about something; it is something. A work of art is a thing in the world, not just a text or commentary on the world…Of course, works of art (with the important exception of music) refer to the real world—to our knowledge, to our experience, to our values. They present information and evaluations. But their distinctive feature is that they give rise not to conceptual knowledge (which is the distinctive feature of discursive or scientific knowledge—e.g., philosophy, sociology, psychology, history) but to something like an excitation, a phenomenon of commitment, judgment in a state of thralldom or captivation. Which is to say that the knowledge we gain through art is an experience of the form or style of knowing something, rather than a knowledge of something…in itself.”

I am partial to Sontag’s reading because, really, how can you divorce a story from the way it is told, a shape from the space both inside and outside it? To perform a dance means to “carry it out,” and carriage needs a vessel, a shape. Form might carry ideas but it does so much more. It charts the boundaries of a work, marks its entrance, allows us in, asks us to stay. Beauty comes to us in arrangements. So do thought and meaning. Water has no shape without a holding.