“Generally I cover stories which I feel are underreported and which need to be told. If I can make some sort of impact to the lives of people whose stories I am covering – that remains my motive.”

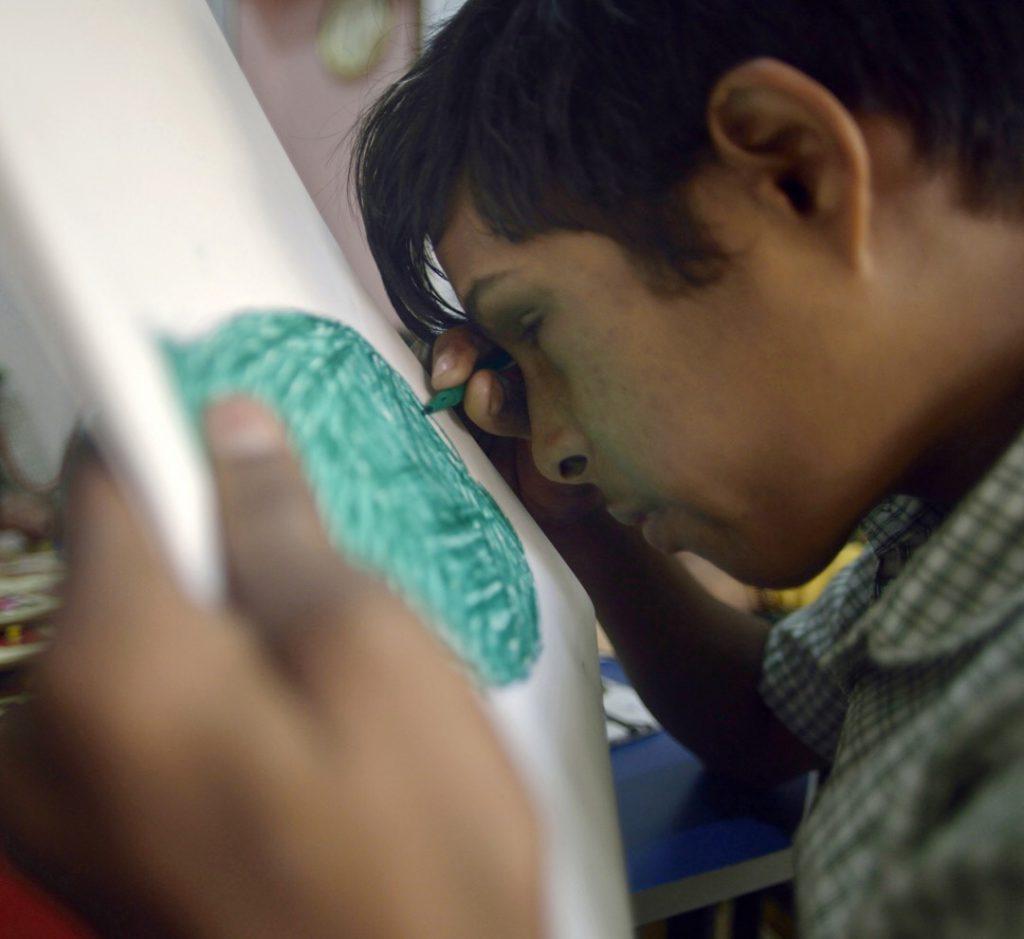

Independent Social Documentary photographer, Rohit Jain, found information on the Bhopal Gas leak story while browsing the internet. He decided to visit the area to understand what happened first hand. “I (like most people) used to think nothing is happening in Bhopal now, everything is normal. The people are living a regular life. I thought I should go and talk to the people who were affected in 1984, find out about the experience they went through. I visited for only 3-5 days initially, and didn’t think I’d spend much time there.”

When he arrived in Old Bhopal in 2018, however, a different story came to light. “When I got to that area, I saw so many children afflicted with various physical disabilities and developmental conditions all in one place, which was very shocking to me. That’s when I decided that I need to document the story from the point of view of these children, young people, and their families. The ongoing effects of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy are very alarming. I decided to do the story from the families’ perspective – the challenges they face in everyday life.”

On the night of December 02, 1984 through to the morning of December 03, approximately 40 tons of toxic methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas leaked from the Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) factory in Bhopal. Spread by the wind, the gas covered roughly 40 square kilometers. All of Bhopal’s population was affected; pregnant women miscarried as they ran, children died in their parents’ arms. In the days that followed, the hospitals were overwhelmed by the dead and dying.

That night eventually ended, but years of death, debilitating disorders, and despair followed.

The leaked chemical waste from the Union Carbide plant had badly contaminated the groundwater, exponentially worsening the situation. A report by the Indian Institute of Toxicology Research (IITR) states that the contamination has spread to over 18 colonies in the area. After several petitions by advocates and activists, the Supreme Court in May 2004 ordered the state government to provide clean drinking water supply to the area. However, consequent action on this did not take place until 2014.

© Rohit Jain

© Rohit Jain

The combination of poisoned ground water and toxic gas have left Bhopal with three generations of people suffering from diseases and disabilities caused by the gross negligence of big corporations and lack of accountability from the state. Today, 35 years later, children are still being born with a range of disabilities not seen anywhere else in India. Cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy (MD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Down Syndrome, visual impairments, learning disabilities, and developmental disorders are common. Many of the children (now young adults) have multiple conditions.

Rohit started by walking around in a 3-5 km radius area from the Union Carbide plant, visiting homes. A lot of people (journalists, charities etc.) visit these families. Some of the community members have naturally become skeptical of outsiders coming in and talking to them – as nothing really changes in their lives. “I didn’t want to give them false hope. It was challenging initially, as some people were reluctant to talk to me. They would say, “Many people come from around the world, but nothing happens.” But, I continued to visit them, have conversations and build relationships. I told them that I want to cover the stories from the lens of the children and their lives, focusing less on the tragedy and more on the ongoing human challenges. Their daily struggles, the bond they share with their children. That was my idea. And when I spoke to them at a personal level, spent more time with them, they began to slowly accept me. I would meet maybe one or two families in a day. The experiences they shared with me were extremely troubling.”

He shares some of the stories of the children and young people documented in his series. Umar Khan suffers from muscular dystrophy, and he needs 24 hour care. Rohit shares, “If there’s a mosquito sitting on his forehead, he can’t simply swat it away”. He had a younger brother who also suffered from muscular dystrophy and passed away last year. Umar can foresee the same fate for himself. While Umar can speak, there are many children who are speech impaired. “So I asked him (Umar) what he does when he has to go to the washroom and no one is around. He said ‘Bhaiiya I wait for some time, maybe 30 mins, till someone comes. Sometimes I end up soiling my pants.’” Umar is 24.

Umar Khan, 24 | © Rohit Jain

Aaliya, 14 | © Rohit Jain

14 year old Aaliya, also struggles with developmental disorder and muscular dystrophy. She lost her mother to gas poisoning eight years ago, and now her father is her sole caretaker. He has to be with Aaliya at all times as she needs constant physical support. He also takes her to rehabilitation sessions at Chingari Trust, an NGO working with the survivors of the Bhopal disaster. When Rohit asked her father why he doesn’t find a special school for his daughter so that he is able to work and earn, he said, “‘No one can take care of Aliya better than me, and Aliya can’t live without me. This is my destiny.’ Despite such difficult circumstances, the kind of bond they share with their children is really heartwarming to see – it filled me with a lot of positivity,” says Rohit.

“The way they have taken these challenges in their stride in a very positive way – it’s amazing. I mean these are difficult things to accept! That has been the most inspiring part for me through this year. Itne pyaar se unki dekh bhaal karna, har cheez ka dhyaan rakhna (looking after them with so much love, taking care of every little detail). Really in that moment when you’re there, it brings tears to your eyes. It gives you courage to handle struggles, accept things in life, and move through it.” Rohit remembers a photograph he kept out of the exhibit, as it was blurry, where the mother of a 22 year old young boy was feeding him, and next to him, his 10 year old cousin was trying to help her. “It was so moving. Now I’m thinking why did I remove that picture, I should have kept it actually. I took it then for that moment.”

Of course doing such a story requires a great amount of grit and resilience. For Rohit too, there were moments of doubt and hopelessness where he almost considered giving up on the project. “When I started doing this whole story I began to feel really depressed about the whole thing. There were points when I felt like ‘I just can’t do it anymore, it was too sad’. I felt like I was evoking some kind of pain in the families again, opening up old wounds that I wouldn’t be able to do anything to heal. I just felt really low.” He had to take a break for a couple of days, during which he reached out to his friends, mentors, and seniors to seek support. “They told me ‘Rohit, this is your work. You have to tell their stories. If you feel bad, then who will do this’. I realised that I could help disseminate their stories to garner support, so that more people could reach out to help them.” With this he found the courage to continue.

As per various reports and articles, neither the government, nor Union Carbide have taken full responsibility for the disaster or even accepted the negligence due to which such a tragic mishap took place – ruining hundreds of thousands of lives. According to a recent article in The Wire, while nearly 50,000 survivors have been compensated since the tragedy in 1984 around 48,000 claimants are yet to receive their payments – 35 years on. The Independent has reported in February 2019 that the Indian Government now recognises that 574,000 people were poisoned, of which nearly 5400 died.

5 years after the disaster in 1989, the settlement overseen by the Supreme Court of India saw Union Carbide (now wholly owned by US multinational Dow Chemical) pay out a total of $470m (GBP 367m) in compensation. According to the same article in The Independent, however, Union Carbide has not paid a single rupee till this day, to almost 470,000 people who were gas affected. Activists say the agreement reached 30 years ago was inherently unjust because it played down the numbers of the dead and injured. Some families were given compensation as low as INR 25,000, staggered over five years – nowhere near enough to sustain their lives and especially the ongoing medical treatments required.

Rohit says, “another major motivation of mine was to raise this issue on an international level, and get people to start talking about the Bhopal Gas Tragedy again. So that we as a society remain alert to how the negligence of the government and big corporations can ruin lives of so many people. There is so much institutional apathy towards issues like this. We have become so desensitised and self absorbed in our own daily lives that we don’t stop to think about such things. There is no proper medical or financial assistance available to these families. As of now, nothing can be done, except that concerned authorities provide this assistance. They should also provide better water and sanitation systems. These are basic things we can advocate for as citizens.”

Rohit hopes to initiate a dialogue among urban audiences that come and engage with the photo exhibit. “That’s how I wanted to bring people together, stir debate, and thereby pressurise the government.”

Back in 2008 or 2009 at the age of 22, Rohit had decided he did not want to do a corporate job. “I wanted to get into activism and pursue a creative field – travelling and writing. There were many things on my mind. I just had a feeling since childhood that I can’t do a usual corporate job, because I won’t be able to tap my potential there. Independence was the motivation,” he says. He got a chance to do a government survey for Ministry for Rural Development in villages in Uttar Pradesh. There he saw a high level of casteism, poverty, and sickness. “At the time I had a small compact camera and started clicking pictures. That’s when I realised I should do this! This is something that will help me tell people’s stories.”

Rohit’s work focuses on human and life development photo stories and he uses photography as a form of activism. Aftermath: 35 Years After The Bhopal Gas Tragedy is a pictorial presentation of the lives of those who have suffered gravely due to corporate and governmental greed. These stories act as a reminder to all of us that we need to be vigilant and aware of decisions made by corporations and governmental bodies that impact our lives and land for generations. “I want people to see this work and I hope it stirs us towards building a collective conscience. We cannot allow another such disaster to occur.” He has received a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting for the series.

Curated by Method Art Space, this is the first time this series is being presented as a photo exhibit at G5A. Rohit hopes to have his work reach more and more audiences through this exhibition. He is around until December 22 at the G5A Study – so do come and engage with the stories and have a conversation with the artist as well!

Words by Sukriti Sharma