When the East India Company, which administered Bombay during the colonial period, first gained possession of the seven islands, English officials noted that the archipelago had natural advantages that would benefit trade. As the nineteenth century European traveller, D. Aubrey, wrote in his travelogue, Letters from Bombay, the Company “strengthened and enlarged the castle and fort of their settlement of rock, jungle and swamp, encouraged native manufactures of cotton and silk, and the lagoon made way for a harbour.”

Bombay’s emergence as a global port city was closely bound up with two commodities, opium and cotton. For the last hundred and fifty years, Bombay’s cotton mills have been the geographic and commercial heart of the city, first through the value they generated through manufacturing, and more recently through the value of land on which they stand. As Aubrey noted, by the late nineteenth century, the urban landscape of Bombay was characterized by “corrugated iron roofs of its manufactories, its peaked warehouses, the hydraulic cranes, the steam drags,” which bore testament to the implementation of modern industry and commerce.

In “Letter XXI – A Cotton Mill,” written on Thusday, 21st June, 1883, Bombay, Aubrey described a visit to one of Bombay’s approximately fifty mills:

Room succeeded room, disclosing vistas of innumerable twirling wheels, sliding bands, revolving shuttles, throstles, mules, roving and slubbing frames. Bobbins vertiginously revolved on innumerable steel needles, and cotton, dirty and gritty when placed at one end of the machine, fell out at the other whiter than salt. Soft, white substances, soft as eiderdown, were wrapped around rollers; masses of fluff flew about, and over steel plates, white materials slided like ice on a thawing stream. The countless threads hanging from all parts of the frames looked like the meshes of a colony of stupendous spiders.

Aubrey believed that “the mills here, paying a low rate of wages, and with large supplies of cotton quite close at hand, would soon under-sell the products of Lancashire throughout the world.” However, a hundred years later, prolonged labour strikes in the 1980s eventually brought production in most of the mills to a halt. As the bulk of Bombay’s economy had gradually moved towards the service sector, mill-owners began to see their land, valued at thousands of crores, as having far more potential than the factories that had fuelled manufacturing.

Throughout its history, Bombay and its citizens have been perpetually starved for space. The Development Control (DC) Regulation of 1991 offered an important opportunity for both mill-owners and the city. Regulations granted permission to the mill-owners to sell their land with the provision that one-third of their plots would be reserved for public housing and another third for open space and civic amenities. As Naresh Fernandes writes in City Adrift, “Since Girangaon’s fifty-four mills stretched out over 600 acres in the heart of the island city, this was the chance for the congested city to breathe again and house its poor in dignity.”

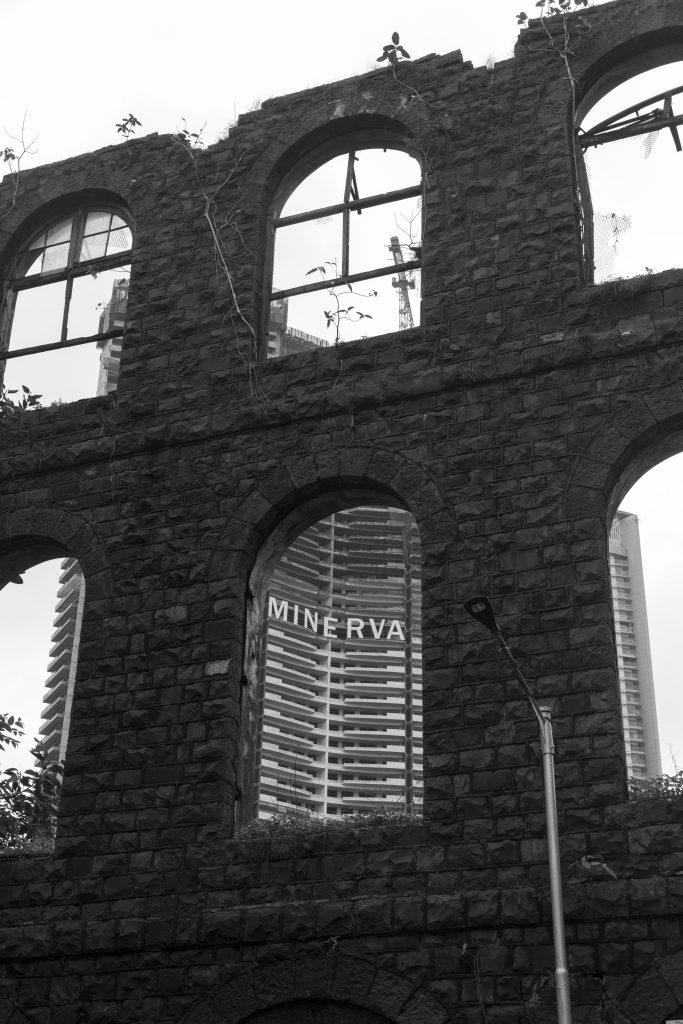

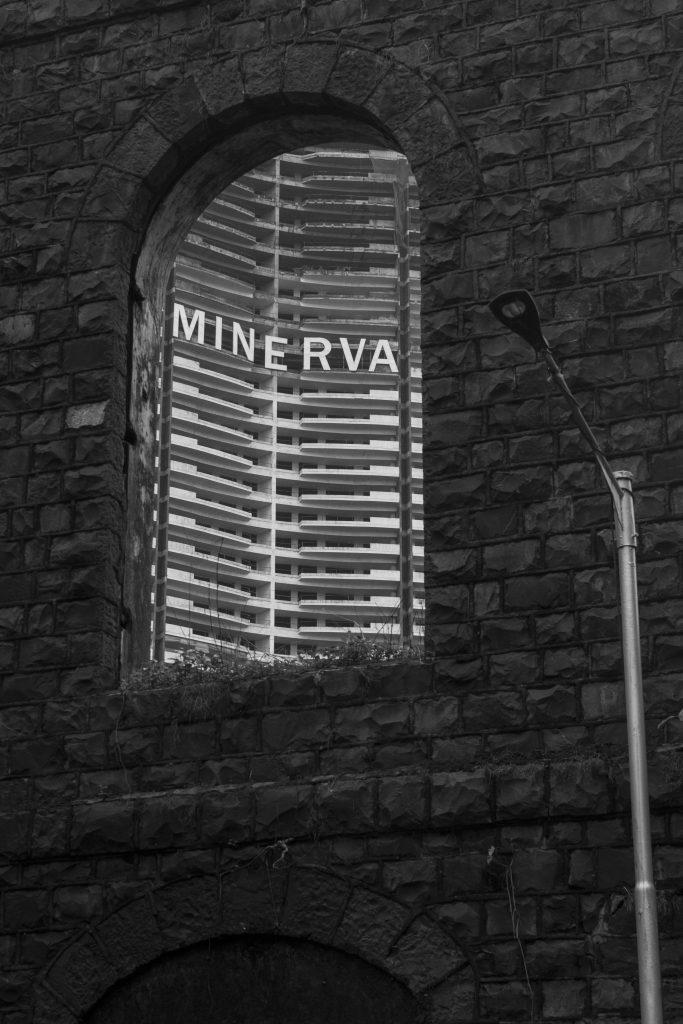

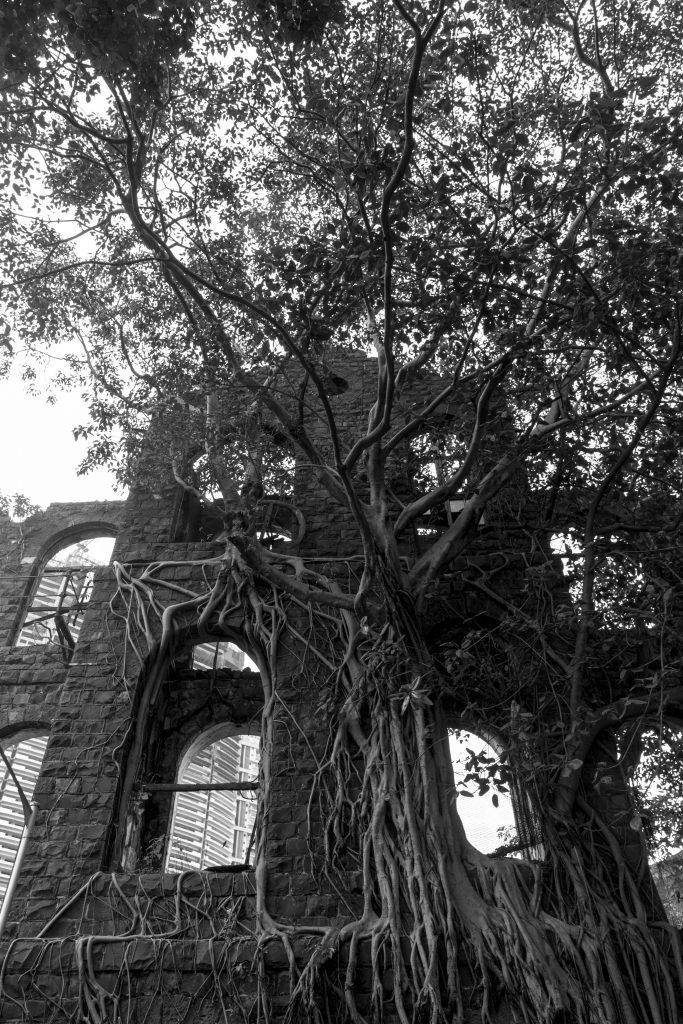

However, caveats in the DC rules and subsequent amendments to regulations stipulating mill land sales have given us the neighbourhoods of Parel, Prabhadevi and Tardeo as they are today: overdeveloped and poorly planned. What was once a skyline of chimney stacks has given way to high-rises, and construction cranes across the erstwhile mill lands are visible from all over the city. Around the Race Course at Tardeo, buildings are literally climbing on top of each other to compete for views of the open green and the sea beyond it. At closer quarters, the derelict facades of Shakti Mills provide windows through which to view the changing priorities and aspirations of the city.

The mills, factories and stores that had once served as symbols of the city’s colonial modernity are now giving way to offices, commercial shopping centres and luxury residential apartments.

When the mills were at the height of their manufacturing power, Girangaon, the village of the mills included areas across neighbourhoods of Tardeo, Byculla, Mazagaon, Reay Road, Lalbaug, Parel, Naigaum, Sewri, Worli and Prabhadevi. In contrast to the well planned neighbourhoods such as Fort in the south, Girangaon was congested and had unsanitary conditions and a lack of basic utilities. Workers in mills and ancillary industries lived in housing blocks known as chawls, which had a series of one-room apartments and cramped living quarters.

While today, office complexes clad in glass and aluminium, malls and gated communities are pushing out many descendants of former mill-workers from their homes, unfortunately, the stark differences existed in the nineteenth century as well. Leaving the major thoroughfares of Fort and walking into the Native Town would have been like being transported into another world. With a distinctly Orientalist tone, Aubrey wrote, “As one penetrates inwards, the wide streets narrow into lanes with native names, the remarkably pure air blowing up from the sea becomes perceptibly heavy with the normal smells of an Oriental city.”

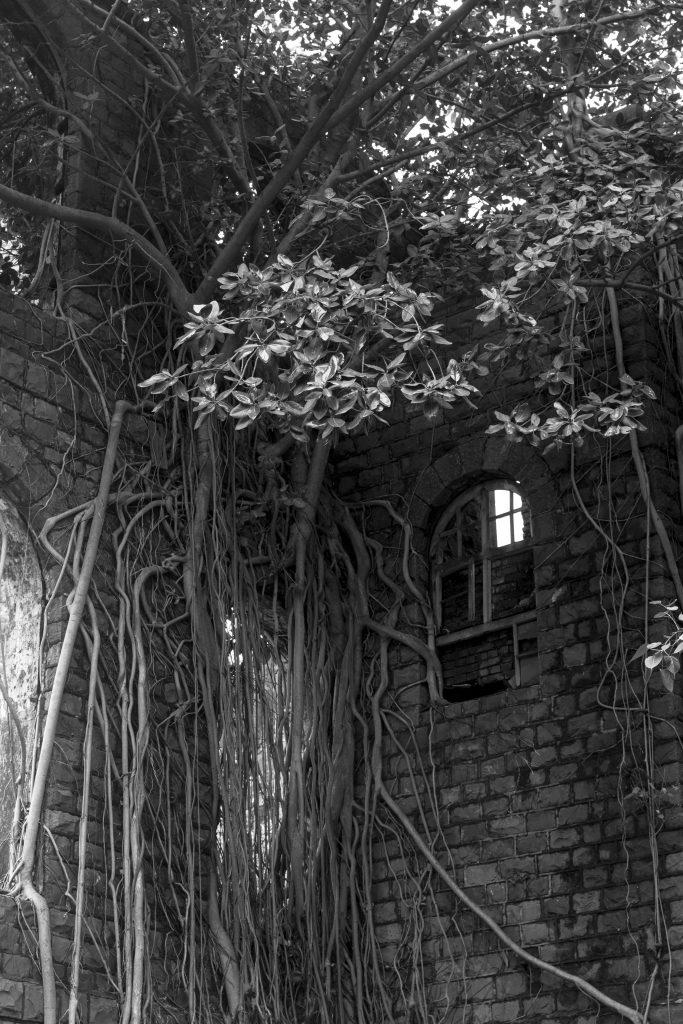

Bombay’s early commercial aspirations, much like many modern developments transformed the city’s ecology. Aubrey wrote, “factories, mills, and huge stores had everywhere replaced the forest and jungle, and peaceful homes now covered spots but fifty years since the lair of the wild beast.” Some of those very same mills that had replaced the jungle are now site to urban regeneration. Magnificent banyan trees have grown into the bricks and stones of derelict mills, dropping their roots from the sky and forming canopies over lanes that would have once been bustling hubs of commerce.

These photographs have been used to create a series of digital artworks that aim to start a conversation about the fluid visual landscape of the Maximum City. They will be presented at a forthcoming exhibition at G5A